TL;DR: RASP is a tensor processing language which provides a language to hand-write transformers. In this report, we survey the main features of RASP and how these features can be leveraged for synthesis. The synthesis task is formulated as a regression task given a synthetically generated dataset of input-output examples. Several complications arise while attempting different synthesis techniques. Overall, I tried Bottom up synthesis, top-down synthesis, and library learning. I'm still working on the library learning experiments!

Section 1: Motivation #

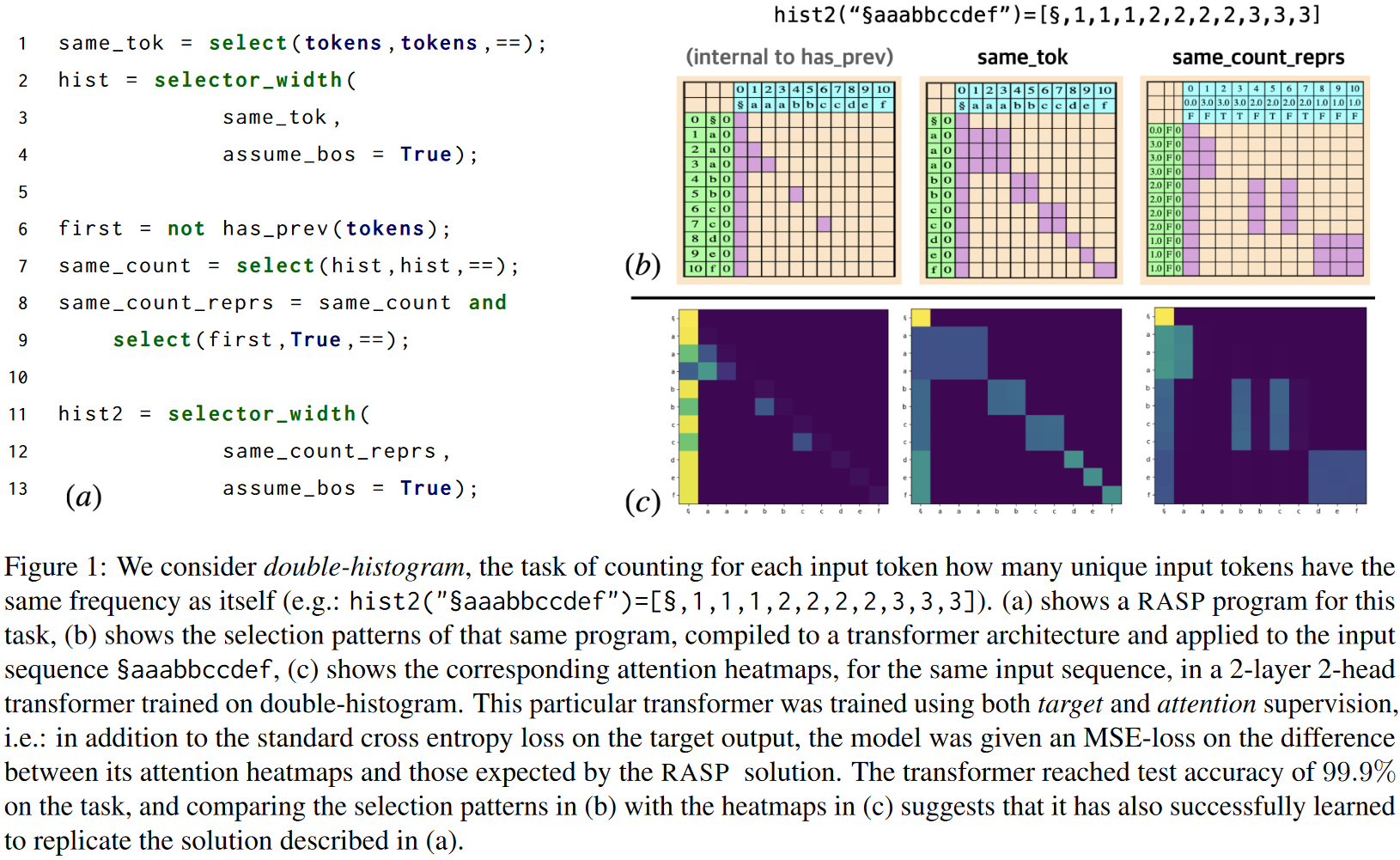

Transformers are feed-forward neural networks that specialize in modelling sequences. They have been extremely successful in NLP and Computer Vision because they make little to no assumptions about the input sequences and, consecutively, model large datasets of sequences very well. However, it is extremely hard to debug such networks and understand their inner workings. One recent approach offers a way to do this by postulating an automata for the transformer model[1]. This automata, encoded as a programming language called Reduced Access Sequence Programming (RASP), allows an expert to handwrite a program that perform sequence-to-sequence transformations. This figure, from the original paper, gives a brief overview:

The authors of this project are interested in distilling a transformer architecture to an equivalent program in RASP. To do this, we will use program synthesis where the specification is in the form of a transformer architecture and a dataset of input examples to generate a dataset of input-output pairs.

Section 2: Introducing RASP #

Reduced Access Sequence Programming is a custom programming language that was presented at ICML2021 as a formal way of reasoning about the inductive biases of a transformer. The authors of RASP take a constructionist approach in designing the programming language. That is, RASP aims to directly model the salient operations of a transformer. Because the focus is on interpretability and correctness, features of transformers that only exist to improve robustness and trainability such as Dropout and Layer Normalization are left out from the base programming language. I shall first define the base builidng blocks of a transformer encoder, then describe how they are modelled in RASP, and finally show RASP working on a toy example.

Introducing Transformers #

A transformer encoder is a feedforward neural network that consumes a list of input tokens and transforms them into a list of output tokens. A functional signature of a transformer looks like this: $f(X_{T \times d_e }, \theta) \rightarrow \hat{X}_{T \times d_e}$, where $X$ is an sequence of input tokens and $\theta$ are the parameters of the neural function. This formulation lends itself very well to modeling sequence to sequence operations. Phong et. al, 2022 [8] give an excellent review of the different transformer algorithms used in sequence to sequence modelling. A transformer encoder and decoder module coupled together allow the transformer to be trained in an unsupervised fashion (Vaswani et. al, 2017). Here, I reiterate the salient features of the transformer encoder used in (Vaswani et. al, 2017):

-

Input Representation: A transformer encoder takes in a sequence of tokens as input. The partitioning is task dependent and can either be on a per-character level, per-morpheme level, or per-word level. For example: assume sentence "Well typed programs don't misbehave". A character level tokenization will look like

[<START_TOK>, ascii(w), ascii(e), ... <END_TOK>]. A word level tokenization will look like[<START_TOK>, word2vec("well"), word2vec("typed"), ... <END_TOK>]. In general, we have a token embedding matrix $\mathbf{W}_e \in \R^{d_e\times N_v}$ ($d_e$ is the size of each word embedding vector, $N_v$ is the size of our vocabulary) from which we can derive each embedding token $\mathbf{e} = \mathbf{W}_e[:, v]$. -

Positional Encoding: We do not explicitly bias the neural architecture of the transformer encoder towards word positioning (this could be different for different languages. Think English word order v.s Arabic word order). Instead, positional encoding is treated as part of the input representation. Hence, we define a positional embedding matrix $\mathbf{W}p \in \R^{d_e\times l{\text{max}}}$ ($l_{max}$ is the maximum length of a sequence) from which we can derive $e_p = \mathbf{W}_p[:, l]$.

-

Scaled Dot-Product Attention: At a high level, attention attempts to model how different tokens interact with each other. It does so by learning a reweighting function that is a linear function of the input tokens and the contextual tokens. "Dot-product attention" specifies the procedure for attention modelling: by taking the dot product of two transformations of the input/context sequences. "Scaled dot-product attention" further specifies that the attention matrix will be re-normalized. This gives us the following algorithm : $$ \text{Scaled Dot Product Attention} :: \mathbf{X} \rightarrow \mathbf{Z} \rightarrow \mathbf{Attn}\ \begin{align*} \mathbf{Q} &\leftarrow \texttt{nn.Linear}(\mathbf{X}) \tag{$\mathbf{X}$ is matrix of input tokens}\ \mathbf{K} &\leftarrow \texttt{nn.Linear}(\mathbf{Z}) \tag{$\mathbf{Z}$ is matrix of context tokens}\ \mathbf{V} &\leftarrow \texttt{nn.Linear}(\mathbf{Z}) \ \mathbf{S} &\leftarrow (\mathbf{K}^\top \mathbf{Q}) \cdot \frac{1}{\sqrt{d_s}} \tag{$d_s$ is dimension of $\mathbf{S}$}\ \mathbf{Attn} &\leftarrow \mathbf{V} \cdot \texttt{softmax}(\mathbf{S}) \end{align*} $$

-

Feedforward blocks: We allow the network to model token-to-token manipulations using multi-layer perceptron's of a fixed size with dropout and layer normalization.

Features of RASP #

RASP uses these salient points to build a programming language that captures the inductive biases present in neural networks.

- Input Representation: The RASP paper uses a character-level tokenization of the input by default. This can be changed to a sentence or a specific delimiter based tokenization by the user. Specifically, the input to RASP is a fixed length array of string's (

List<String>(LEN)). It is assumed that the output will also be a fixed length array of string's. This guarantees that the number of tokens remains the same. - Positional encoding: Transformers concatenate the input tokens and the positional encoding for the token before feeding the input into the transformer encoder. The logical equivalent of a concatenation operation here is passing a pair of fixed length string's through the program where the first element is the input string and the second element is a list of indices for each element in the string. RASP relaxes this paring. RASP constructs two built-in functions

tokens :: string -> list<string>andindices :: list<T> -> list<int>to allow access to the tokenized representation and the indices at any point in the program. - Scaled Dot Product Attention: Attention is a matrix multiplication between the selector matrix $\mathbf{S}$ and a linear interpolation of the contextual tokens. RASP realizes this as a select-aggregate operation. The select operation consumes two sequences of the same type and produces

- Feedforward blocks: RASP allows the user to write functional element-wise tensor manipulation programs called sequence operators (abbreviated to s-ops).

tokensandindicesintroduced earlier are the simplest s-ops. RASP offers overloaded bindings for most python primitive functions.

Here, we list out some of the common RASP primitives:

1---------------------

2-- RASP Primitives --

3---------------------

4

5T = string, int, float

6

7--- Sequence Operators ---

8s_ops ::=

9 {- Built in s-ops -}

10 tokens :: string -> list<string>

11 indices :: list<T> -> list<int>

12 length :: list<T> -> list<int>

13 {- Tensor processing operators. Tensor-tensor operators are applied elementwise following python semantics, tensor-constant operators convert the constant to a filled tensor and follow tensor-tensor dynamics. -}

14 round :: list<float> -> list<int>

15 + :: list<T> -> list<T> -> list<T>

16 / :: list<T> -> list<T> -> list<float>

17 < :: list<T> -> list<T> -> list<bool>

18 ...

19 {- Tensor interaction operators. This is inspired by dot-product attention.-}

20 select :: list<T> -> list<T> -> (T -> T -> bool) -> matrix<bool>

21 aggregate :: matrix<bool> -> list<T> -> list<T>

22

23{- A lot of python constructs such as `def`, `dict`, and `list` are overloaded to make it easy to manipulate programs. This is not part of the base RASP language and only to help organize code. -}

A Running Example #

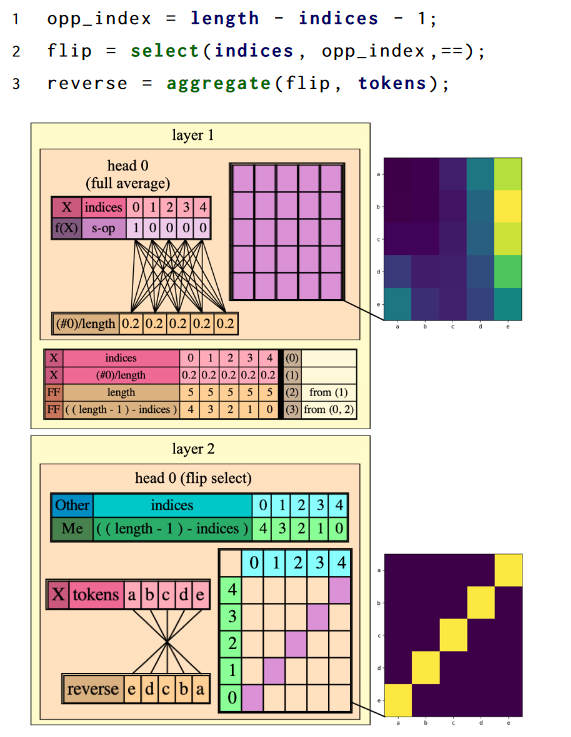

Let's take the example of reversing a sequence of tokens. Specifically, we want to make a function reverse('xyz') = 'zyx'. This can be implemented using a subset of the constructors we introduced above:

1def reverse(input_string='xyz'):

2 tokens = tokens(input_string)

3 indices = indices(input_string)

4 length = length(input_string)

5 reversed_indices = length - indices - 1

6 reversed_mat = select(indices, reversed_indices, ==) # Each element is `i == len - j - 1`

7 reversed_str = aggregate(reversed_mat, tokens)

8 return reversed_str

9

10def flattened_reverse(input_str='xyz'):

11 return aggregate(select(indices(input_string), length(input_string) - indices(input_string) - 1, ==), tokens(input_string))

RASP Compiler: The authors provide a compiler that converts a RASP program to a partial transformer architecture. Briefly, they replace each select-aggregate block with a single-head attention block, initialized to match the select-matrix's weights. They aggregate s-ops on a per-layer basis and replaced with a trainable MLP. A "full" compilation would require calculating the weights of the MLPs. The authors did not implement this.

Making a differentiable approximation of RASP allows us to use neural guided synthesis techniques. We do this on a per-function basis.

Section 3: Transformer Synthesis #

@TODO: Three sections here. First, problem definition/ Second, experiments using NEAR. Third, experiments using Dreamcoder and finding common abstractions with Stitch.

There are four features of RASP that make it amenable to synthesis:

-

Functional Language: Programs in RASP do not have loops or conditionals and can be expressed as compositions of functions on the input sequence. Notwithstanding let expressions (variable declarations), we don't need to keep track of a variable environment while synthesizing programs.

-

A (weak) notion of equality: RASP programs can be compiled to an equivalent transformer architecture. This seems to be a many-to-one mapping. This makes RASP amenable to bottom-up program synthesis methods because we can compare equivalence between RASP programs by comparing the (binary) weights of the compiled architectures.

-

Differentiability: RASP primitives are inherently differentiable. RASP is built on top of selector (

select,selector_width) , aggregator (mean,sum), and comparator (and,le,leq,eq) functions. All these functions have good approximate continuous relaxations. This means that RASP semantics can be re-implemented to make a differentiable programming language. This allows us to use top-down program synthesizers that evaluate partial programs and use neural networks to guide the search (such as NEAR[2] and dPads[3]). -

Compositionality: Programs in RASP are inherently composable. This allows us to reuse abstractions important for a particular task in other tasks. For instance,

length-- one of the primitive s-ops -- requires two select-aggregate-sequence-operation blocks in our RASP implementation. It exists as a built in abstraction because it is extremely important for implementing complex functions. Other such structures might exist that we can leverage to learn a library of abstractions.

These properties allows us to use three classes of synthesis methods 1) Bottom-up synthesis, 2) Top-down synthesis, and 3) Library learning.

Problem Definition #

Given:

-

$\mathcal{L}$: The domain specific language. In this case RASP and derivates of RASP.

-

$\mathcal{D} = {\text{task}i, \mathbf{X}^{(i)}, \mathbf{Y}^{(i)} }{i=1}^{T}$ A dataset of tasks with input-output sequences for each task. ie: $\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{Y} \in \R^{N\times e_d}$.

-

$\phi$ = A set of satisfiability constraints. In this case, this is a differentiable loss function for regression tasks (

torch.nn.functional.mse_loss)

we want to find a architecture $\alpha \in \mathcal{L} $ with parameters $\theta$ that obeys the following constraint: $$ \min_{\alpha, \theta} \sum_{i=1}^{T} \phi(\alpha, \theta, \mathbf{X}^{(i)}, \mathbf{Y}^{(i)}) $$

Bottom-Up Inductive Synthesis #

Within bottom up synthesis, we posit many programs starting from the terminal nodes and combining them in different ways. This problem is notoriously NP-complete (PSPACE I think? TODO) but, in practice, is pretty fast because bottom up synthesis is embarrassingly parallelizable. The challenge with bottom up synthesis is that the language should implement a notion of equality between different programs so we can prune semantically equivalent candidates. RASP showed initial promise of having a notion of equality because the program can be compiled to an equivalent transformer architecture. However, after careful reading through the paper, we realized that RASP's compiled transformer doesn't initialize the MLPs. This is problematic for defining a notion of equality because MLPs, as universal function approximators, admit a large class of semantically similar functions. This severely reduces the efficacy of equality based pruning and, consecutively, reduces the efficacy of bottom up synthesis itself.

Instead of probing this concept further, I decided to use a different class of synthesis algorithms instead.

Top-Down Inductive Synthesis #

Next, we decided to use a neural guided search algorithm for finding programs within RASP. We procedurally generated datasets used in the RASP project for training transformers for top-down inductive synthesis.

DSL Changes: I had to modify RASP to allow gradient backpropagation. This required using continuous relaxations[4] for certain functions. I describe all the changes made below:

-

T = float | bool. I reinterpret the string processing tasks as integer manipulation tasks instead. This is more of a design choice because the original NEAR implementation cannot handlestring's and I would need two implementations ofF.mse_lossfor the search procedure. -

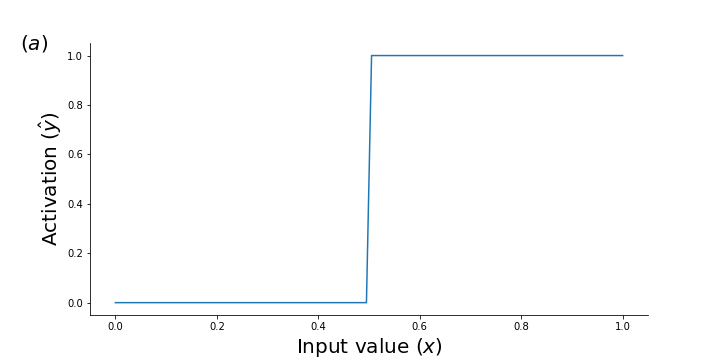

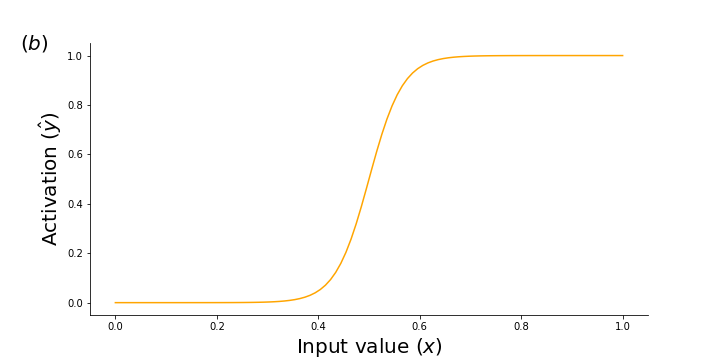

operation :: list<T> -> list<bool>: Any function that outputs bool's is replaced with a shifted sigmoid function. The figure below shows a continuous relaxations of the> :: T -> T -> boolfunction implemented as a shifted sigmoid function with high temperature (10) : $\hat{y} = \frac{1}{1 + e^{-10 (x -0.5)}}$.greater_than(0.5) soft_greater_than(0.5)

-

select :: list<T> -> list<T> -> (T -> T -> bool) -> matrix<bool>: I decided to implement this as a hard KQV -attention operation instead. In pseudocode: $$ \textbf{Hard }\text{Scaled Dot Product Attention} :: \mathbf{X} \rightarrow \mathbf{Z} \rightarrow \mathbf{Attn}\ \begin{align*} \mathbf{Q} &\leftarrow \texttt{nn.Linear}(\mathbf{X}) \tag{$\mathbf{X}$ is matrix of input tokens}\ \mathbf{K} &\leftarrow \texttt{nn.Linear}(\mathbf{Z}) \tag{$\mathbf{Z}$ is matrix of context tokens}\ \mathbf{V} &\leftarrow \texttt{nn.Linear}(\mathbf{Z}) \ \mathbf{S} &\leftarrow (\mathbf{K}^\top \mathbf{Q}) \cdot \frac{1}{\sqrt{d_s}} \tag{$d_s$ is dimension of $\mathbf{S}$}\ \mathbf{Attn} &\leftarrow \mathbf{V} \cdot \phi(\mathbf{S}) \tag{$\phi = \begin{cases} \texttt{gumbel_softmax }& \text{train time} \ \texttt{argmax2d} & \text{test time} \end{cases}$}\ \end{align*} $$ This is done solely to increase the training performance of the network. -

aggregate :: matrix<bool> -> list<T> -> list<T>: This is implemented as a batched matrix multiplication (torch.bmm).

NEAR Changes: I implemented this in NEAR and defined a "typed" neural network depending on the type signature of the "hole":

| Type signature of hole | Neural network relaxation implementation |

|---|---|

hole :: T -> T |

feedforward MLP with ReLU activation |

hole :: T -> bool |

feedforward MLP with a sigmoid activation and a softmax normalization. |

hole :: list<T> -> list<T> |

An RNN implemented as a bidirectional GRU block. |

hole :: list<T> -> list<T> -> matrix<bool> |

scaled dot-product attention |

Results: NEAR wasn't able to discover any meaningful programs. Here is the performance for the reverse task.

-

(Assumed) Ground Truth Program:

Aggregate(Select(LinearSelectIndices, LinearSelectLength - LinearSelectIndices, AtomToAtomLessThan), LinearSelectTokens). This exposes some of the internal details of the implementation however, the general idea is that NEAR allows selecting any linear combination of the base s-ops which then feeds to an aggregate+select combination. -

Program Found:

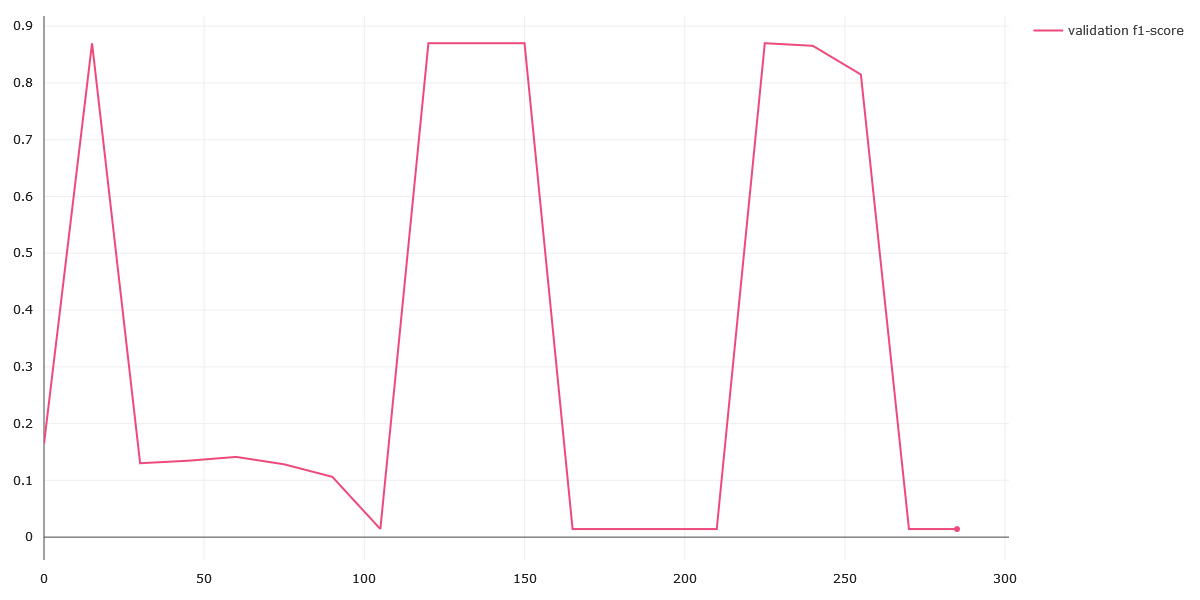

ListtoListModule. :upside_down_face:. This is equivalent to running an RNN on the input features (the indices, length, and the tokens). The model isn't able to find a complete program until timeout (5 hours). I've included the graph for the validation score through the synthesis process of the program architecture evaluated. The peak's correspond to when the model is evaluating some rotation ofListtoListModule(such asAdd(ListtoListModule, ListtoListModule)):

-

Analysis: NEAR ranks functions in the DSL depending on their structural cost, current program depth, and the heuristic cost. The assumed base program is actually very hard to find. Assume the partial program

Aggregate(Select(?, ?, ?), ?). This partial program has a high structural cost (because we need to initialize 4 leaf nodes) and high depth cost (because there are a lot more depth 2 programs that can still be explored). At the same time, the RNN guided the model towardsList -> Listtype functions. I believe that I would eventually reach the base program but it must take more than 10-12 days of compute time (which is not feasible).

Overall, NEAR suffered from the fact that the DSL is made to be used in an imperative programming style where variables defined earlier are reused. I considered manually adding in useful combinations of functions (such as SelectAggregateBlock :: list<T> -> list<T> -> list<T> to the DSL to speed up NEAR's synthesis. However, instead of doing this manually, I figured that library learning might be an interesting technique to automatically extract common sub-structures.

Library Learning #

I use dreamcoder for library learning. Dreamcoder consists of three phrases:

- Synthesis: The current DSL is used to synthesize programs for the tasks given.

- Dreaming: The learned programs and program hallucinations are used to retrain the recognition network.

- Abstraction: The learned programs for each task are analyzed for common sub-structures. These common sub-structures are extracted and added to the DSL.

I ran out of time this semester to run the entire dreamcoder pipeline. For this report, I only talk about the experiments I did to finetune the Abstraction phase of dreamcoder for RASP.

Specifically, I hand-curated a list of RASP programs (from the paper) and rewrote these programs in a lisp-like form that Dreamcoder can consume. Here are some sample programs:

1;; Length

2(length $0)

3;; indices

4(indices $0)

5;; Running mean

6(aggregate (select indices indices <) tokens);

7;; Length

8(round div one (aggregate (select one one ==) (indicator (eq indices zero))))

9;; Reverse

10(aggregate (select (indices $0) (sub (sub (length $0) (tokens $0) one)) less_than) (tokens $0))

The original OCaml program compressor struggles to find even simple abstractions (select-aggregate). This is an inherent limitation of DreamCoder. Instead, we use Stitch[7] to find abstractions. Stitch leverages the dataset of tasks and finds abstractions that maximally fit across tasks. This works well in finding common abstractions across tasks. Here is an example of the abstractions found for this dataset.

1{

2 "body": "(aggregate (select (indices #0) #1 less_than) (tokens #0))",

3 "dreamcoder": "#(lambda (lambda (aggregate (select (indices $1) $0 less_than) (tokens $1))))",

4 "arity": 2,

5 "name": "fn_0",

6 "rewritten": [

7 "(lam (length $0))",

8 "(lam (indices $0))",

9 "(lam (fn_0 $0 (indices $0)))",

10 "(lam (round div one (aggregate (select one one equals_to) (indicator (eq (indices $0) zero)))))",

11 "(lam (fn_0 $0 (sub (sub (length $0) (tokens $0) one))))"

12 ],

13

14}

We are the first "end-user" of Stitch besides the authors. However, Stitch, currently, cannot integrate into the DreamCoder loop (yet!). I am currently working with the authors of Stitch to make this integration.

Section 4: Conclusion #

Overall, I tried synthesizing programs using top-down synthesis , bottom-up synthesis, and library learning. Library learning seems the most promising because we already have a corpora of program abstractions that we can leverage to solving more problems. However, Stitch is not ready to be used with DreamCoder. In fact, I was the second Stitch user (after the authors).

I'd love to pursue this topic as a serious research problem in the future.

Relevant Material #

[1] Thinking Like Transformers https://arxiv.org/pdf/2106.06981.pdf

[2] Neural Admissible Relaxations https://arxiv.org/abs/2007.12101

[3] Differentiable Synthesis of Program Architectures https://openreview.net/forum?id=ivXd1iOKx9M

[4] Smooth Interpretation https://www.cs.utexas.edu/~swarat/pubs/pldi10.pdf

[5] TF-Coder https://arxiv.org/abs/2003.09040

[6] Programmatically Interpretable Reinforcement Learning https://proceedings.mlr.press/v80/verma18a/verma18a.pdf

[7] Top-Down Synthesis for Library Learning https://arxiv.org/abs/2211.16605

[8] Formal Algorithms for Transformers https://arxiv.org/abs/2207.09238